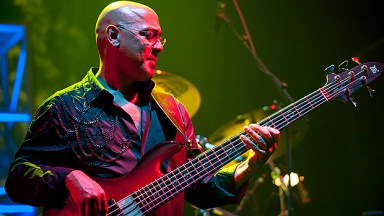

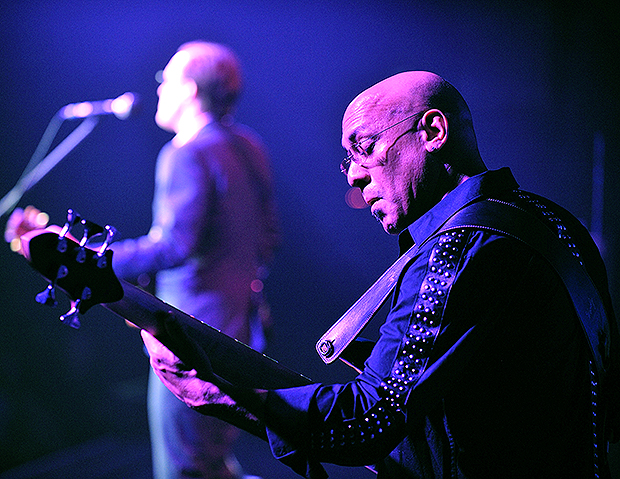

Carmine Rojas takes us back, going four decades into the past, when he saw David Bowie in person for the first time. “It’s comical a little bit, to be honest with you,” Rojas says to HollywoodLife when reflecting on that first meeting, right before the bassist would join Bowie’s band to begin work on what would be the “Space Oddity” singer’s most commercially successful album of his career: Let’s Dance. The album celebrates its 40th anniversary in 2023, and Rojas will be part of the celebration at the David Bowie World Fan Convention 2023 (June 17-18 in NYC).

Rojas, who had worked with Labelle and Nona Hendryx in the 1970s, recalls how he ended up meeting with “The Thin White Duke” in a studio in New York City. “I got a call on a Friday to be at Power Station Studio on Monday to do a session for Nile Rodgers,” Rojas tells HL. “I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll come in.’ We all know each other; we’re all from the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens. I show up Monday, and as I walk in, I don’t know which studio or room [to go to]. I walk into the one off the elevator to the right and take a peek. I see people in there, and we have this thing in New York, we go like, “You big old-looking mother–ker.” I just ramble something like that. “David Bowie looking MF.” And it’s hilarious. Just top of my head, ‘big old David Bowie-looking mother–ker.'”

“It was the facial features, and this guy had a cap on, but the face was pretty much the same,” he explains. “I walked out and looked around, and the assistant engineer came around and said, ‘Hey Carmine, you’re in this room.’ I said, ‘Oh, cool. Who’s that big old David Bowie-looking mother–ker?’ He says, ‘That’s David Bowie.’ And I started laughing. I actually laughed. He said, ‘No, that’s really David Bowie.’ And I went, ‘What’s he doing here?'”

“My whole thing demeanor changed,” says Rojas, adding how it was strange to see David Bowie at the Power Station studios at around 10 in the morning on a Monday. The engineer informed Rojas that he was working on a private project with Nile Rodgers and Bowie. Rojas remarked how Rodgers had said nothing about Bowie’s involvement. “He kept it really private,” Rojas tells HL, “because they want to keep it very private all the way around.”

“I walk into the room, and it’s really him! And I’m a big fan because I’ve seen the White Light Tour and I’ve seen the second half of the Diamond Dogs Tour ’74 and ’76. And I knew some of the crew guys. I’ve been a big fan of Carlos Alamar. He’s been like a mentor. I look up to him being Puerto Rican. That’s the guy, as kid Latin musicians, we looked up to Carlos because he crossed Latin into English rock and roll. And it was a big deal to us. Wow.”

“I wasn’t sure that I had to courtesy bow or we weren’t really sure what to do,” remarks Rojas. “Here he is in front with this beautiful smile, this cap on, and he just says, ‘Thank you for coming, for being involved in this project.” And I’m thinking, ‘Is this real?’ For me, it was. It’s like running into Paul McCartney — which happened at one time at Manny’s Music store. There are a few people that make me nervous. David made me nervous. Paul McCartney made me nervous but Paul McCartney, I couldn’t speak. David at least I was trying to.”

When Rojas found his words, he asked what brought Bowie to Hell’s Kitchen. “He said, ‘I’m just working on some demos on stuff and seeing where I’m going to go experimenting.’ And to me, experimenting is like, I’m sitting here with Picasso,” says Rojas. For him, the idea of being involved with Bowie during an experimentation process was too good to be true.

“Because in all the other normal sessions, you go in, they’re either fun, tedious, or an ‘I should have never been there’ kind of a thing,” he explains. “But this one, I got thrown in the deep end. Thank you, Nile. God bless him. And many grateful thanks.”

“And was curious what he wanted from us,” continues Rojas, “which I found out later on he wanted urban players, but he didn’t want top session players — not guys who don’t know how to work in the studio or be creative at the same time. Nile handpicked a lot of us that were available, but the phone calls went down the list, and we were available. It was great because Omar [Hakim, drummer] and I worked together as kids in many different bands with Labelle and Nona Hendryx and we all grew up together. It was an interesting team to put together with Nile Rodgers and his keyboard player from Chic [Robert Sabino].”

The makeup of this band was intriguing to Rojas, considering the players’ expertise in funk, disco, R&B, and jazz – genres not immediately associated with David Bowie. “In my head, I’m thinking Station To Station, Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane,” says Rojas. “I have all these images — which is not good to go into because he’s going to take you somewhere else like he always does: every album, every project. You just have to forget what happened in the past. You’re going to be taken to another planet. Me mentally not being aware of that, I just had to sit and wait to see what comes out.”

At the time, Rodgers and Bowie had the demos of what would become Let’s Dance, including the title track. Rodgers had a sketch of where he wanted the song’s bassline to go, but Rojas tells HL he saw the song going in a different direction. “I repeated the bass pattern Nile wanted me to do, and I just kept hearing this other note go somewhere else and I went somewhere else. There are YouTube displays of the original pattern a bit,” he says. “I hear going down this way, and we interpret the rhythm section like the Gap Band because that’s what me and Omar were into back then.”

“And I interpreted it that way and then added other parts to it because the original just stayed in B flat the whole time in B flat area. More like a sheet kind of a thing. Which is great and cool, but I don’t think that’s where David wanted to go a hundred percent.”

However, forty years later, that experimentation remains intact. “I assumed correctly,” observes Rojas.

Rojas says the making of Let’s Dance was a quick affair. “We went in there, and I was only supposed to be there for one day, so we knocked out three songs: ‘Let’s Dance,’ ‘Modern Love,’ and I think, the next day, we did ‘China Girl.’ One take or two takes. David was comfortable with the arrangement. He did reference vocals. We just followed the vocals, and, in my mind, we could have done a lot more stuff. But that’s what he wanted. He wanted to be raw and naked with the mistakes, so if he puts a vocal of himself, if he vocally sings a mistake, he’ll hit a vocal with link to the mistake, and it’ll be proper. So if you make an error or whatever, he’ll use that bum note for the vocal link, and wow. That was clever!”

“Watching the process of him and how he worked, [he was] very calm, knew exactly what he wanted,” continues Roajs. “Nile and him were great together. And we were just kids looking around going, ‘Okay, I’m just going to turn 30, and I’ve done a couple of sessions on my belt but nothing like this. Nothing on this level. Dreamt about that level, but here it is on my lap.’ And I had to really be somewhat conscious of where my maturity was at the time, which wasn’t great, but I’m still growing as we all are. And what you do is you let go in those kind of situations. You let Picasso and Dali do what they do and just try stuff because in those moments, with those kinds of artists, you can experiment with stuff and let them dictate.”

However, while Rojas was comfortable letting Bowie dictate, Bowie wasn’t a dictator. When recording Let’s Dance, Bowie was around 35 years old, slightly older than Rojas – who was reaching his thirties. Bowie acted as a mentor to the younger band. “I’m very fortunate to be gifted that at that moment in time,” says Rojas, “to let someone manipulate or, for lack of a better word, someone maneuver what’s inside my head and saying that it’s cool and it’s okay. Just the validation, where it’s coming from, and it could have been a complete lie, but obviously it wasn’t. [Bowie] knew my potential a lot more than I did.”

“He knew how to dig, which is easier for someone else to dig into your head. It’s like sharing your secrets with people you don’t even know that you feel comfortable with. And with him, it was comfortable to fully let go and let him force me around.”

The results of the work paid off. Let’s Dance was a commercial smash. The title track reached No. 1 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100, where it stayed on top for nine weeks. It remains his best-selling album, seven years after Bowie’s death in 2016. The title track, as well as “Modern Love” and his cover of Iggy Pop’s “China Girl,” are some of Bowie’s well-known and best-loved songs.

Rojas said that it was easy to work with Bowie. Not only was he able to trust David with steering where the music was going, but Rojas was already involved with listening with a lot of prog rock bands – Genesis, Yes, Traffic – as well as the bands from the sixties that helped Bowie develop his own musical sensibilities; “I understood some of his background — some, very little of it because his mind was… He never felt glowing,” says Rojas.

“He was always a gentleman, and he was always sharing his education, sharing what he knows very beautifully. It was just easy to follow him around and not be so engulfed but still learn again like a mentor. A lot more of that came out once I did the tours,” says Rojas, who would continue to play with Bowie on the Serious Moonlight and Glass Spider tours that would follow Let’s Dance. “I could see him in action, how he controls the audience, how someone can do a hundred thousand people and being the front and control that massive into a positive situation.”

“It was a wonderful place to be. It was awesome,” he remarks. “He was very free with his intelligence and his behavior, his wonderfulness, his goofiness. Very great comedian, very dry humor like a Mighty Python. To spend the time with someone like that, real-time for my interpretation because there were guys who spent a lot more years with him — but the little time that I’ve had with him, for seven years, it was awesome.”

That awesomeness continues to this day. Working with Bowie changed Rojas. “It did trigger [something in] my head that, what I’m doing, where I’m going in my route — with him or without him — it’s possible. And coming from where I come from a Puerto Rican neighborhood out of Brooklyn, it’s possible. And I get a lot of messages from South America, from Spain, all the other Spanish countries, people looking up to me. And you always have to pay it forward. Whatever you do in life, you have to pay whatever you learn, you always pay it forward, and it comes back, and I don’t know. Like I said, I was in the right place at the right time and mentally ready to be thrown in the deep end and the deeper end and then come out of it, teaching back or giving back love. It really is basically a love thing with music.”

Rojas speaks with gratitude for his time with Bowie. He would play on the following two albums – Tonight and Never Let Me Down – before Bowie would change again, forming and disbanding Tin Machine before entering the ’90s.

“He knew how to focus us into a situation to get what he wanted at the time and moments with him,” says Rojas, “either he’s there, or he is not there. He’s focusing on something like a painting, like an abstract painting. You have to always remember, he doesn’t write for others, he writes for himself. He doesn’t care whether you like his shit or not. If it relates, cool, if it doesn’t, somebody else is going to relate to it.”

“The second album [Tonight], ‘Loving The Alien,’ all that stuff — we were experimenting a lot of stuff in the room. It’s like, ‘Wow, I’m on the single [‘Blue Jean’]’ Tina Turner [who sang on the title track]. There were so many different relationships going on at the time. It was an open canvas. You come in, no preconceptions, just walk in. ‘All right, David, you get your leash on; where are we going? Where are you going to take us to?’ And it’s a fun adventure. You just never know what the outcome’s going to be. It’s beautiful to be able to work like that with someone.”

Catch George Murray and more — including Carlos Alomar, George Murray, Tim Palmer, Robin Clark, and more— at the David Bowie World Fan Convention 2023, taking place at New York City’s Racket on June 17-18.