Years before meeting him, George Murray’s idea of David Bowie was that the “Fame” singer was larger than life. Literally. “My first impression of meeting him was a lot different than my first real impression of him is as a personality,” George tells HollywoodLife ahead of his highly-anticipated appearance at the David Bowie World Fan Convention 2023, taking place at New York City’s Racket on June 17-18. “Which,” says Murray, “was what I saw before I started working with him at a billboard that RCA had put up on 6th Avenue in Manhattan with the release of Diamond Dogs. And my reaction was, ‘What is this?'”

That image was likely the album’s artwork by artist Guy Peellaert which depicted Bowie as a half-human, half-dog sideshow act. “I had heard ‘Space Oddity,’ [it’s] a nice song, but I hadn’t really followed him to see that image of him. It was, I don’t want to say shocking, but it was unique and thought-provoking,” shares Murray. “So when I first met him, he was nothing like that. He had advanced for a number of years, but I met him at a rehearsal studio where I was asked to come to California to play on the Station To Station album, which looking back, was really a live audition for me.”

“But the first time I met [Bowie] was at a rehearsal studio,” he adds. In 1975, Murray had flown out from New York at the request of his Bronx Community College friend, drummer Dennis Davis, and guitarist Carlos Alomar. “Dennis, Carlos, and I met him at a rehearsal studio in Hollywood on Cahuenga Boulevard. And that’s when he walked in as a regular human being and shook my hand and said, ‘Hi, I’m David.'”

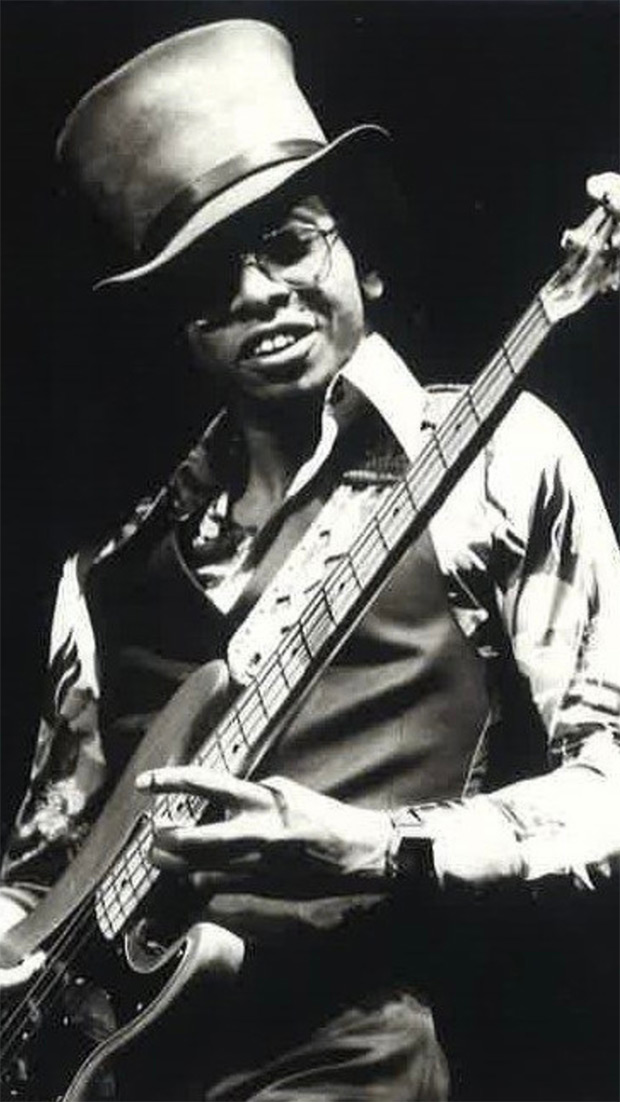

From there, George Murray played bass in one of Bowie’s most creative periods. After Station To Station, which Rolling Stone says has “some of the greatest songs of Bowie’s career,” George continued to play with Bowie as part of the D.A.M. trio, helping Bowie shape the albums of “The Berlin Trilogy” – 1977’s Low and “Heroes” and 1979’s Lodger – as well as 1980’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps). Though commercial and critical reception was mixed at the time, the albums would go on to revolutionize rock and inspire future generations of musicians, to where the albums are now regarded as some of Bowie’s best.

It’s George’s bass we hear on “Sound and Vision,” “Golden Years,” “Heroes,” “Fashion,” and “Ashes To Ashes,” songs that have come to define Bowie’s legacy in the wake of his 2016 passing. However, George Murray speaks about his time with Bowie with warmth, sweetness, and remarkable humility.

After Scary Monsters, George transitioned out of the music industry as he focused on starting a family – which required a steadier income and a steadier presence at home. For the past four decades, he’s lived in California, working in education. As to why this man hasn’t toured the press circuit and sold a handful of tell-alls about witnessing Bowie at arguably his creative zenith, Murray tells HL a story about his time in the band that influenced his decision to respectfully stay out of the spotlight.

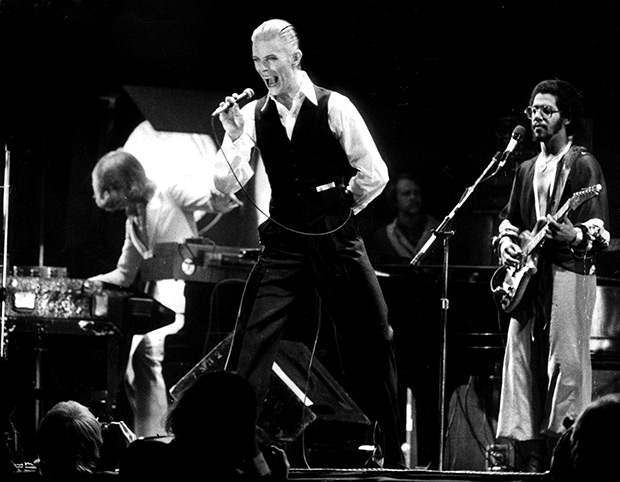

“David had a road manager, and I don’t quite remember what all the circumstances were, but the band was — we were not necessarily demanding, we weren’t acting spoiled or anything. We were just young men wanting to do stuff in their time off. And the road manager reminded us, ‘The tour is moving ahead because of David’s schedule, not yours. Nobody’s buying a ticket to see you. They’re buying a ticket to see him. And that’s the way we’re going to do it.’ Bing. I’ll always remember that.”

“And that stuck with me as a young man trying to get ahold of my emotions, impulses, and insecurities, and all the other things that went along with it at that time,” continues Murray. “And so I stepped back. And I took that to heart and developed the perspective that I am there to support. I am there to perform, I am there essentially to fulfill my responsibilities to the position and to make the person in front, who has chosen me as part of the ensemble, go out and entertain and enthrall the people at each performance.”

This doesn’t mean Murray didn’t feel valued during his time with Bowie. “Yes, definitely,” he tells HL. “David chose the musicians in his band very carefully, and I think he was, in fact, I know he was, he was pleasantly surprised with the way that they functioned together as a group, as an organism.”

“But, there was a degree of separation mainly because of schedules and movements and things like that,” he adds. “He was moving in some circles that we were not, most of which we were not in at the same time. But when we did see each other, it was friendly and personable, enjoyable, always intellectually stimulating in one way or the other. Because David, he knew a lot of stuff that I didn’t, and I enjoyed it.”

Murray credits Carlos Alomar as a mentor and “the person who helped me through it a lot” during this time. Carlos worked as David’s band leader for at least two tours before Murray arrived. “And David had a great degree of trust in Carlos to interpret and project to the band members what he was trying to get across,” says Murray. “Because that relieved him of that responsibility of ‘how to do that, how do I communicate with all these different individuals as opposed to just one and having him take care of it?’ Which he did, Carlos was instrumental in that respect.”

“As what [Bowie] might have thought of me, I didn’t know. And it was a little unsettling because there’s a degree of, I should say there’s a lack of confidence that I’ve carried with me through my many years, it’s part of my nature. And I knew Carlos, I knew Dennis, and I played with them before, but not in that arena, I should say. So, I didn’t get a whole lot of feedback from David. I got feedback sometimes from Carlos, but I didn’t really get a whole lot of positive or negative, it was more personable, and it was neutral.”

“So I didn’t really know if he liked what I was doing or little things here and there, [Bowie] might ask for through Carlos to have the guys do this, but I didn’t know how he felt about me,” reflects Murray. “I just know I’m supposed to be someplace at a certain time. That’s where I’ll be, and that’s what I’ll do. And that’s where Carlos and Dennis are going to be. That’s fine. We’ll be there, and we’ll do what we have to do or what’s required at that time.”

“I had known Dennis and Carlos before enabled me,” he continues. “At least I had someone to speak with and bounce ideas off of. And Carlos helped me a lot through that time.”

As Murray shares, Carlos Alomar would also be instrumental in getting him on Bowie’s world tour – along with Bob Denver…sorta. “What really brought on some anxiety when word was circling around that [Bowie] was planning to go on tour in January, we were now in September,” begins Murray. “And his business manager had spoken to several people about going on tour with David, but I wasn’t one of them. And he had done it at different times. So it wasn’t like he was talking to everybody at once except me, it wasn’t like that. It was he would grab you when he saw you, or he was passing.”

Murray says the anxiety was building and came to a point one evening when he had a “very interesting conversation” with his friend. “Carlos was a practicing Buddhist at that time, and I knew that. Dennis used to make fun of him or tease him, but Carlos and his wife Robin were practicing Buddhists of the Nichiren sect,” says Murray.

“The Nichiren sect is, just in general, that’s the sect that chants, ‘nam-myoho-renge-kyo,'” he explains. “Those are amazing words, but anyway. Essentially the take was you chant ‘nam-myoho-renge-kyo,’ you can get what you want or get anything you want. So Carlos and I are sitting in my hotel room one evening, and I don’t know your cultural reference, but this is 1975, September. There’s a show on TV called Love American Style. We’re watching an episode with Bob Denver, who went on to play Gilligan in Gilligan’s Island, and [60’s sex symbol] Joey Heatherton.“

“She was playing this type of ‘Hippie chick,'” says Murray. “Bob Denver was trying to make a connection with her. He was trying everything, nothing was working. Joey Heatherton’s character says to Bob, ‘Well, why don’t you chant ‘nam-myoho-renge-kyo’ and then see what happens.’ So he tries it. We’re seeing that right there on the TV. And at that moment, I said, ‘Carlos, I know you chant. Can you tell me something about that?'”

“Carlos looks at me and says, ‘I’ve been waiting to tell you, I just haven’t had the opportunity yet,'” says George Murray with a smile. “So we went through the basic theory and some terms and things. He says, “Well, chant’ nam-myoho-renge-kyo,’ if you really want to go on tour, you’re not sure what’s happening, chant ‘nam-myoho-renge-kyo’ and see what happens.”

“So I did,” says Murray. “Next day, nothing happened. I think it was the day after that, or I was walking somewhere either in the hotel or down the hall of Cherokee Studios, and [the business manager] says, ‘Oh, George, by the way, you doing anything from January through June of next year?’ I swear! And I said, ‘No, I’m fine.’ He said, ‘Well, David wants you to do the tour. Can I put you down?’ I said, ‘Of course, you can. Thank you very much.'”

“And that’s the way it worked out way,” he adds. “I continued chanting from that moment on. I’m still a practicing Buddhist. I still chant every day.”

Murray also shared how Bowie approached the bass as an instrument and his own playing. “When Dennis, Carlos, and I were playing, sometimes David might have been playing piano or guitar for a scratch track to go along with it. The music was going onto the tape really straight and natural,” says Murray. “Sometimes [we used] some forms of electronic compression and equalization, things like that. But nothing to change the sound or the character. Those things happened, I think, later on in the mix or editing when David was working with producers.”

Bowie “molded [the bass] and shaped it after the natural sound was down,” he shares. “I didn’t use any effects. I might have toward my later albums with him. But I think that was all David’s concept. I was experimenting with sounds in live performances, how to make the bass sound different, how to make it sound heavier or thinner. Some effects I was working on that were available at the time, flanging and phasing. And that was essentially the extent of it.”

“It was most evident, I think when we reproduced ‘Heroes’ on stage,” he says, “because at that time I was playing a bass with an aluminum neck because I wanted that. It was called a Travis Bean, and the fingerboard was wood, but the actual neck was made of aluminum. And the overall effect was a brighter sound, but a brighter sound that didn’t lose the bottom. So when I sent that through a flanger and adjusted the EQ on the amplification, I had a very unique sound.”

The songs that George Murray played on have become ingrained in everyday life. His bassline has helped laid the foundation for modern rock – as well as post-punk, alternative, and countless other nebulous genres. Chances are, we will hear George’s playing sometime this week. “Hearing ‘Golden Years’ at the grocery store, that was enjoyable,” he says. But George, humble and grounded, never draws attention to the fact that it’s him playing.

“I might have if I saw someone was captured by the music at that moment, but usually people aren’t, not in that environment,” he says. “Every so often, that one, and ‘Ashes to Ashes,’ I hear that a lot. And, ‘Heroes,’ sometimes, ‘Heroes.'”

“And I was flattered when the producer put the full version of ‘Heroes’ at Earl’s Court in Moonage Daydream,” he says, referring to the 2022 movie detailing Bowie’s life, “because everything else was just pieces of things, but that was the full song. You could tell that was an anthem being played to the stadium. And I loved it. I loved it.”

Catch George Murray and more — including Carlos Alomar, Carmine Rojas, Tim Palmer, Robin Clark — at the David Bowie World Fan Convention 2023, taking place at New York City’s Racket on June 17-18.